When disco music fell out of favour at the dawn of the 1980s, jazz prodigy Patrice Rushen became pivotal in ushering in a new era of post-disco and boogie — offshoots of the cast out genre that James Mtume, Reggie Lucas and Kashif also had a hand in moulding.

Under Elektra Records, Patrice would release a string of albums that pushed R&B forward without sacrificing its roots. Floor-fillers like ‘Hang It Up’, ‘Haven’t You Heard’, ‘Never Gonna Give You Up (Won’t Let You Be)’, ‘Feels So Real (Won’t Let Go)’ and ‘Get Off (You Fascinate Me)’ were demonstrations of a new sound that synthesised all of Black music’s past and ultimately prophesied its future. Patrice characterised the sound as “sophisticated dance music”.

In 1982, Patrice was vaulted into eternal pop music ubiquity with the release of her seventh album ‘Straight From The Heart’. Best known for featuring her signature song ‘Forget Me Nots’, which would be famously sampled on Will Smith’s ‘Men In Black’ and George Michael’s ‘Fastlove’, the seminal body of work was also home to the timeless cult classics ‘Remind Me’, ‘Number One’ and ‘Where There Is Love’. Forward-thinking in its approach, ‘Straight From The Heart’ saw Patrice at the height of her powers as a pop music provocateur.

Read this next: Eight emerging artists who are changing the sound of soul

Patrice Rushen’s under-discussed influence on contemporary pop culture can be traced through the many future classics she influenced. Her material continues to be a never-ending reservoir for those partial to sampling. Kirk Franklin, Mary J. Blige, Mobb Deep, Zhane, Shabba Ranks, De La Soul, Musiq Soulchild and Ty Dolla $ign are just few of the artists who’ve turned to Patrice’s work as a North Star. When listening to her back catalogue, it’s striking how audible the foundations for the development of neo-soul, smooth jazz, quiet storm, dance-pop and house music are within her music.

Shifting tastes and creative differences with labels would eventually cause Patrice to step away from life as a front-facing artist. Her esteemed pedigree as an accomplished multi-instrumentalist and arranger meant she stayed a powerful force behind the scenes, including making history as the first woman to work on The GRAMMYs and The Emmys as a musical director. Patrice has since expanded into the world of academia, serving as an ambassador for artistry in education at the Berklee College of Music and teaching at the USC Thornton School of Music, where she is chair of their popular music program.

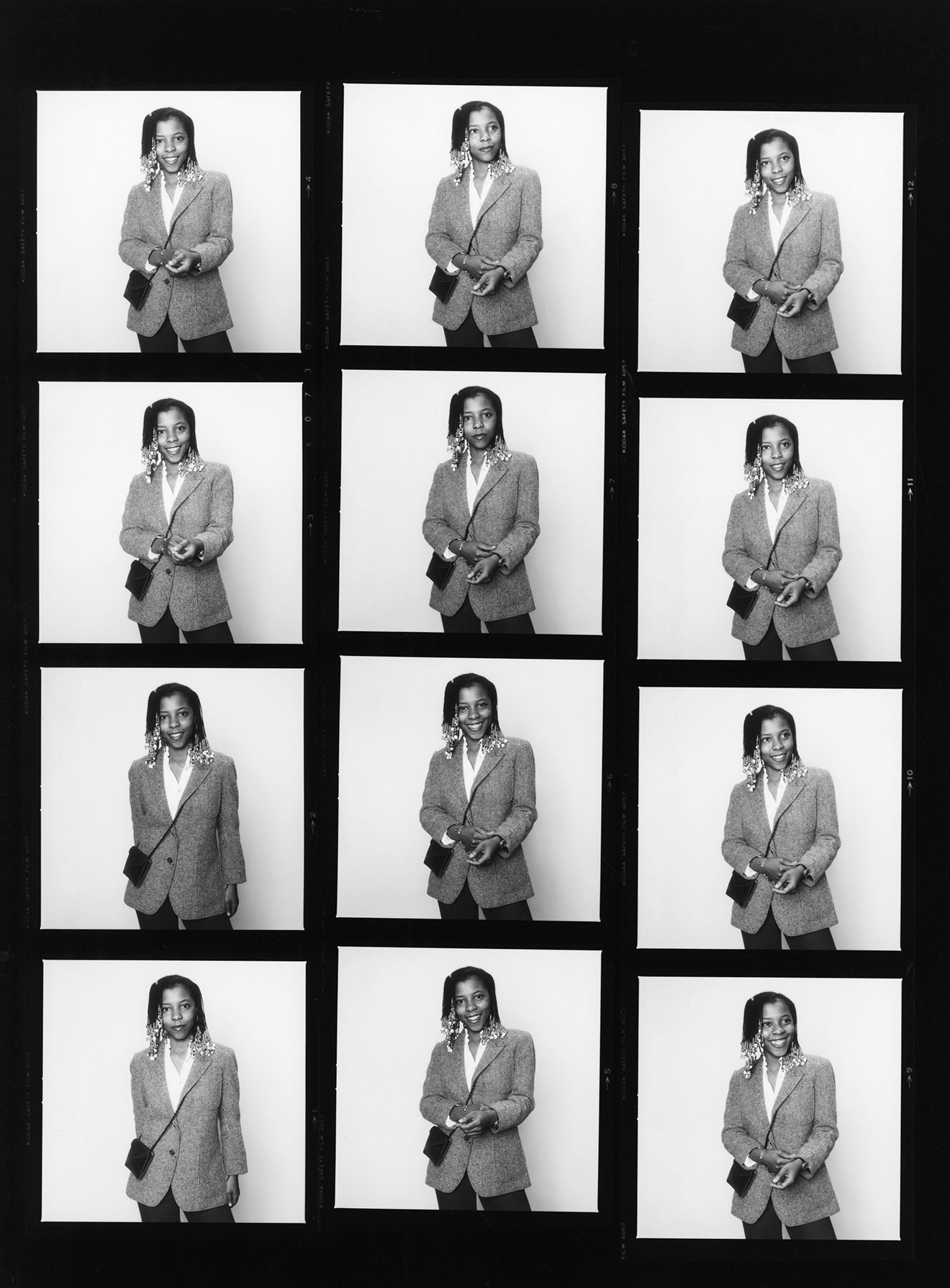

In the lead up to her recent UK shows at KOKO and Cross The Tracks, we caught up with Patrice to reflect on her polymathic career.

This year marks the 40th anniversary of your landmark album ‘Straight From The Heart’. What are your memories of that time?

Nothing but happy memories. I always had such a great time in the studio with my friends. We weren’t going for hits per se or thinking about formulas, we were just doing the music we liked to do. It was a little different for its time. Slightly ahead of the curve in terms of what was on the radio back then.

’Forget Me Nots’ was met with nothing but disdain by the record company. They said, “We don’t get it. We don’t hear any hits on this album. Nothing”. Yet that’s the album that has ‘Remind Me’, ‘Number One’ and of course ‘Forget Me Nots’. All of which are among my most recognisable songs.

For us it was a positive reaction, because if we really believed in it, then we would have to show that we were willing to stand by it. We can’t make people love it, but it needed to get in front of them for them to be able to decide. Black radio at the time was a particularly big deciding factor for Black artists. I was always looking at it like “What do my people think first?” — making sure that the material got to radio and that the people who listened could weigh in on what they were hearing.

We put our money in, and it blew up to the point that the label gave back the money we spent on independent radio promotion. That album and that song in particular has really special meaning because here we are 40 years later, and it is still being used, sampled and danced to everywhere. Now even on TikTok!

Tell me about the creative process behind ‘Number One’, and ‘(She Will) Take You Down To Love’?

When I was getting ready to start writing that album, ‘Number One’ was the first thing that I wrote. I wanted to show that there could be this melding of groove that was danceable and infectious, but still have harmony with nice changes and progressions. A great arrangement that kept people interested but had improvisation, which was part of my jazz roots. I didn’t feel like any of those things were mutually exclusive. We called it ‘Number One’ so we could move on and the name just stuck.

With ‘(She Will) Take You Down to Love’, I had a real fascination for the music of South America – particularly Brazil. I just was playing around on the guitar, and found this feel that I thought was cool. I had become friends with the actress Fay Hauser-Pryce who was in the movie Roots. She was a real lover of music, so I asked her to take a stab at writing some lyrics and she came back with what you hear. I wanted it to feel intimate, provocative and have that simmering soulfulness. It’s just myself on guitar and Paulinho da Costa on percussion.

Read this next: 10 of the most influential disco labels of the last decade

What was the landscape of Black music in 1982 when the album initially came out?

I think there was a love affair with trying to crossover. The idea of crossing over became a big deal at that time. For some it was a preoccupation and almost an obsession. It was the whole trickle down theory. Theoretically, if you sell more records and get more airplay then you can tour to a wider audience.

There isn’t anything necessarily wrong with that, but people would then alter who they were in order to be more palatable to pop radio. Even if it wasn’t a good fit for what they’re about or what they represented musically. Certain artists were able to do that and become more popular, whereas others diminished and dissolved a lot of their uniqueness trying to be something else.

I however, was not worried about that. That came with some good and also some bad. The good news is that when I went into the studio, we went in to do what we loved to do and what we wanted to do. The bad news is that if it didn’t fall into a neat lane, it could be perceived as being too jazzy to be R&B, too Black to be pop or too pop to be Black. I was just trying to do the music that I liked, and as far as I was concerned, it could go to whoever wanted it. To record companies, that would have looked like I wasn’t trying to move up the crossover food chain.

Throughout the ’80s, a lot of music was criticised as there was thought to be too much reliance on synthesisers and the other new technology. The brilliance of your work is that it struck a sweet balance of organic musicianship while embracing the technology. How did you keep that balance?

When synthesisers started becoming more accessible and easier to program, it opened up a completely different palette of colours that could be applied to whatever kind of music that you wanted to do. It was like I had 100 extra colours in my crayon box, that’s the way I viewed it. I had more to experiment with. Having new ways in which to express, expand and animate the musical experience of creating but also listening.

I embrace technology and new instruments because it helps you do things faster and with more accuracy. It also provides more elegance and greater articulation because you can do just about anything. Conversely, just because you can do anything, it’s no excuse to not get it right in the first place. If that’s what you mean to do, get it right! That way, your announcement of that particular thing truly represents what it was you were intending to do.

Raed this next: When signing to a major label goes very, very wrong

You were given a lot of creative control at Elektra Records but the label seemed to always approach your music with trepidation and hesitation when it came to promotion. Did your time at Elektra and eventually with Clive Davis at Arista Records kill your love of making albums and being a front-facing artist?

No, not at all. The public had already given me the highest compliment of all. They were embracing the music without the kind of hyperbole that typically would have to accompany a new release. That said enough to me. That’s what a songwriter or composer wants, acknowledgement that the music that they’re doing is reaching people. And if that can be done organically like it often was, I didn’t take it lightly.

Then it got to a place where it became a contest. The brass ring of more record sales. I was being told if you want to sell more records, here’s what you’re going to have to do. The brakes were put on me being left to my own devices with the confidence that I could come up with a hit on my own. That was my experience at Arista. It was a different company with a different mentality.

Clive Davis was very hands on about what he wanted to see done. He appreciated great talent but he was controlling about the way things would go down. By this point, I had already been nominated for GRAMMYs, seen a lot and more importantly amassed ample respect. I didn’t feel like what he wanted was for me. My philosophical approach when it came to music meant that it didn’t mean that much to me to sell loads of records. I don’t put down people who go down that path, because I know how hard they work. I just didn’t want to do it.

I told him that I was never really going to be what he wanted me to be, and he didn’t want to support what I wanted to do. After my ‘Watch Out’ album, he let me out of the contract. I then went back to what I was trying to do in the first place, which was film scoring. Everything I had done was a route to making that dream happen. I was able to score the cult film, Hollywood Shuffle for Robert Townsend. From there, I was able to work as a music director for the NAACP Image Awards, the Emmys, and eventually the GRAMMYs. I feel it turned a corner on the recording side of things, so for a long time, I just didn’t do it.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.