More conglomerates, venture capitalists and private equity companies are dabbling in our industry, drawn by its potential for growth, tech integration and high engagement rates.

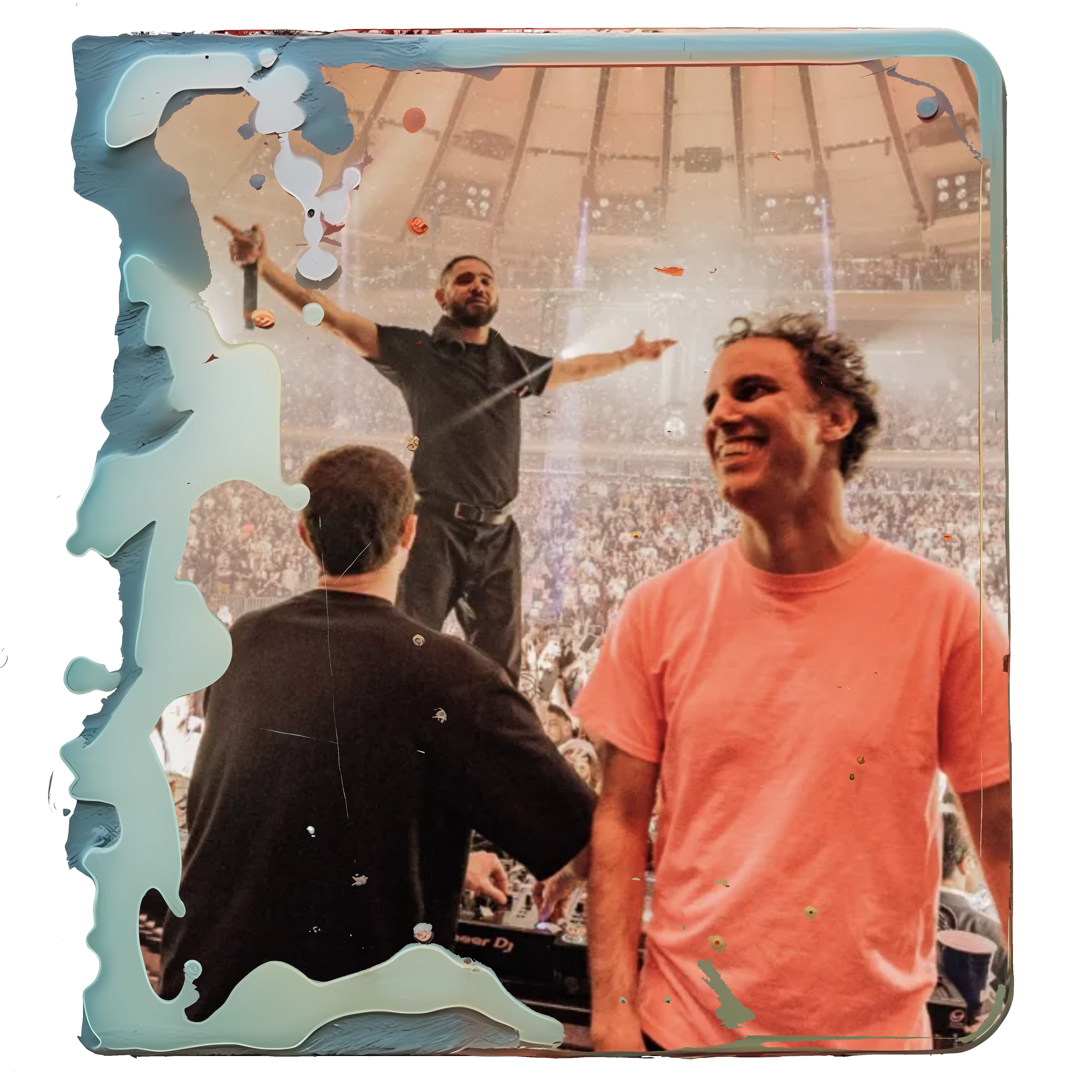

When Skrillex, Four Tet and Fred again.. took New York’s Madison Square Garden by storm in February, investors were paying attention. The trio’s ability to merge fans across the EDM and tech house spectrum in one of the world’s most prestigious venues signalled juicy business opportunities for financiers looking to cash in on dance music’s widening presence in mainstream culture. The sheer amount of content creation on social media from that one show had analysts across the globe speculating on revenue intake from livestreaming, merch sales and brand collaborations, among other possibilities.

As club music increasingly enters popular discourse through TikTok, pop records, luxury fashion houses and high-profile concerts like the Madison Square Garden gig, Big Finance is taking note. Recent years have seen an influx of corporate capital into nightclubs, festivals, promoters and relevant tech platforms as conglomerates, private equity firms and venture capitalists enter the sector for the first time. Industry consolidation is also rampant, with behemoths like Live Nation expanding its grip through acquisitions and stake sales.

French billionaire François-Henri Pinault is reportedly buying a majority stake in Creative Artists Agency, home to Dawn Richard, Daft Punk, Amelie Lens and Eartheater and other electronic artists, for $7 billion from private equity firm TPG. In July, FIVE Holdings, a Dubai-based property development and hospitality group, acquired a $343 million stake in Pacha Group from private equity firm Trilantic Capital Partners. Last year, New York superclub Avant Gardner, cofounded by a Swiss financier, bought local promoter Made Event and its flagship festival Electric Zoo, one of the city’s largest, for $12.5 million.

When Skrillex, Four Tet and Fred Again.. took New York’s Madison Square Garden by storm in February, investors were paying attention.

In 2021, UK-based Superstruct Entertainment, backed by private equity firm Providence Equity Partners, acquired Dutch festival group ID&T for between $150 and $200 million. Superstruct, whose CEO is Creamfields founder James Barton, previously bought a majority stake in Sónar and invested an undisclosed sum in Helsinki’s Flow Festival. That year also saw UK tour operator Mainstage Festivals, backed by investment banking firm Edition Capital, launch a new festival, Inner State, in Albania. Native Instruments also sold a majority stake to US private equity firm Francisco Partners, which has ticketing service Eventbrite and production software provider Soundwide under its belt, in 2021 for an undisclosed amount.

Music industry professionals say these deep-pocketed executives are being lured by high engagement rates, the potential for tech integration, consumer preference for immersive experiences, plus nightlife’s growth trajectory following Covid-19 lockdowns. According to the latest International Music Summit report, the global electronic music industry is now valued at $11.3 billion, versus $8.7 billion in 2019—a strong recovery given how hard events were hit by the pandemic.

While institutional investment can boost employment and widen infrastructure, this flood of commercial cash could raise more risks than rewards. Critics are particularly concerned about the impact on music programming and ticket prices, not to mention dance music’s shift away from its roots in DIY counterculture. Homogenised lineups are already a major complaint and with more profit-minded players involved, the issue is only set to exacerbate, squeezing out independent operators in the process. The resentment among artists and fans is palpable—in 2018, Blawan and The Analogue Cops titled their collaborative EP Hedge Fund Festivals Kill Electronic Music.

“It’s kind of a cat-and-mouse game where corporations are constantly chasing coolness because coolness functions as a different kind of capital,” said madison moore, a DJ, cultural critic and assistant professor at Brown University. “Eagle-eyed trend watchers keep their fingers on the pulse of youth culture so they can capitalise on the next big thing.”

Private-equity backed Superstruct Entertainment, which partly owns Flow Festival, “trusts in our artistic vision and helps us make that into reality,” a spokesperson for the Helsinki event said.

What’s driving the dealmaking?

Corporate consolidation has been a recurring theme in the music industry for decades, particularly among record labels. From Warner Brothers buying Atlantic and Elektra in the ’60s and ’70s to BMG purchasing RCA in the ’80s to the ’00s, when Sony took over BMG and Universal acquired EMI, corporate interests have long controlled recorded music. It’s a similar story with promoters. In the ’90s, New York magnate Robert F.X. Sillerman of SFX Entertainment, a company that ultimately morphed into Live Nation, undertook multiple large-scale acquisitions of independent players.

However, the current surge of institutional investment in nightlife feels different, insiders say. Dealmaking has traditionally focused on certain sectors, but financiers are now looking for avenues that combine various verticals of the music business—labels, festivals, clubs, publishers—while increasing average revenue per customer. “They want a distribution system that’s interlinked with social media, ticketing or other technology services such as livestreaming, AI or VR,” explained Srishti Das, a consultant specialising in music at analytics firm MIDiA Research.

That helps explain Penske Media’s decision to enter the festival landscape. The US entertainment conglomerate, which owns Billboard, Rolling Stone, Variety and other publications, bought a majority stake in SXSW in 2021. The following year, it acquired a majority stake in Las Vegas festival Life Is Beautiful (founded by venture capitalist Tony Hsieh in 2013) through its subsidiary Rolling Stone and launched its own festival, LA3C, in Los Angeles. These projects are likely to benefit Penske’s myriad editorial titles as they become integrated into each festival’s ecosystem. This year, the media empire unveiled its own livestreaming platform, which could be used to broadcast festivals down the line.

During the pandemic, investment was primarily aimed at offline experiences–VR, livestreaming and the metaverse—but analysts say there’s more to C-suite interest than tech. Culture-driven opportunities are especially attractive, particularly how a particular festival or venue impacts youth culture.

“When you attend a festival or a club, it’s a whole experience of enterie,ng the world of that space and exploring that space’s relationship with design, the neighbourhood, food, fashion and non-music activities like tattoos or wellness—it’s a whole cultural experience,” Das noted. “There is a clear demand for identity-driven culture, which is why you’re seeing genres like Afrobeats, neoperreo and amapiano going global. Investors want a slice of that.” Engagement and content are particularly important metrics, she continued. “Venues drive a large amount of user-generated content since the first thing most people do when they enter a venue is take photos and videos for social media.”

The cultural angle is a priority for Rockstar Games. In 2022, the video game giant made its first investment into brick-and-mortar nightlife: an undisclosed sum into UK-based venue operator and festival promoter Broadwick Live, which runs super clubs such as Printworks in London and Depot Mayfield in Manchester. Rockstar Games isn’t a stranger to clubland, having launched virtual nightclubs and radio stations in its Grand Theft Auto games, which feature Moodymann, Solomun and The Blessed Madonna as characters. The company is also spearheading CircoLoco Records in Ibiza.

Speaking to RA, a spokesperson for Rockstar Games said the deal with Broadwick Live was “a logical extension of our desire to find new ways to bring our love and support of dance music and club culture into the physical world, especially in light of the disproportionate impact Covid-19 had on music and culture venues.” Broadwick has previously received backing from UK media giant Global Entertainment, and also operates event rental space Oval Studios in London, formerly beloved club Oval Space, after the latter lost its licence.

Another major development that differentiates the market’s current momentum from previous years is rampant monopolisation. With the pandemic wiping out a massive chunk of independent nightlife operators across the globe—in the UK, 30 percent of clubs have shut since 2020—bargain hunters are on the lookout for deals. Live Nation, whose top shareholders include investment firms Vanguard Group and BlackRock, spent $68.2 million on global acquisitions in 2022 and shows no sign of stopping–its recent targets include Hong Kong’s Clockenflap festival and Colombian techno promoter Páramo Presenta. In 2019, US promoter Insomniac Events, which throws Electric Daisy Carnival and is 50 percent owned by Live Nation, bought an ownership stake Miami’s Club Space.

tu

The now-shuttered Brooklyn venue Output (pictured above) voluntarily closed in 2019 despite resistance from its biggest investors. “Overnight, the Brooklyn market became as over-saturated as London and Berlin, thereby making it economically challenging for us to compete with venues backed by multinational corporations with large sources of capital,” the owner Nicolas Matar said.

“In the major dance music markets today, there’s typically a few dominant players monopolising the booking of big headline DJs,” said Nicolas Matar, a nightlife veteran who opened two of New York’s iconic and now-shuttered clubs, Cielo and Output, both of which were funded by private investors whose capital wasn’t tied to institutions. “These [dominant players] are mostly multinational corporations funded by private equity money—this was not the case one decade ago,” he continued.

Matar, who’s been in the scene for more than 30 years, believes inflated artist fees were a major catalyst for corporatisation. Fees for top-tier artists skyrocketed when Hollywood talent agencies like CAA and William Morris Endeavor (WME) got into the DJ game, he explained, noting how big DJs went from having agents to entire teams. Smaller agencies adopted the same business practices and it became an industry norm, he added. This, combined with fees factoring in a DJ’s ability to sell bottles and VIP tables at clubs, made talent-buying extremely expensive.

“The economics of running an independent venue are very different than a festival or large pop-up event but sadly, the big talent agencies do not differentiate between the two,” Matar explained. “A lot of DJs that played 1,000-capacity events one decade ago now only play 5,000-capacity events and festivals, making it impossible for independent promoters in brick-and-mortar venues to compete.”

Back in the day, Matar’s strong interpersonal relationships with artists enabled him to book DJs like Carl Cox at a price that allowed his venues to turn a profit, pay investors back and always pay employees on time. “Sadly, in this day and age, relationships no longer move the needle when dealing with overzealous agents and artist teams,” he warned.

His Brooklyn club Output, which many believed housed New York’s best sound system, voluntarily closed in 2019 despite resistance from its biggest investors. The decision, he said, was due to a combination of exorbitant artist fees, neighbourhood gentrification, the venue’s no-photo policy in the Instagram era, its lack of bottle service and market oversaturation. “Overnight, the Brooklyn market became as over-saturated as London and Berlin, thereby making it economically challenging for us to compete with venues backed by multinational corporations with large sources of capital,” he said.

For now, developed markets such as North America, the UK and Europe are expected to receive the bulk of corporate funds. “India, South Africa and East Africa are definitely on the map but they lack nightlife infrastructure and scale,” Das said. “For example, 300 people in a UK club is a good number but 300 people in a club in India seems like nothing given the country’s 1.4 billion population.” Emerging markets such as China and the Middle East also have complex tax laws and involve other expenses so growth in those areas must be sufficient for business development to be worthwhile, she pointed out.

In 2022, the Rockstar Games invested an undisclosed sum into UK-based venue operator and festival promoter Broadwick Live, which runs super clubs such as Printworks in London (pictured above) and Depot Mayfield in Manchester.

What are the implications?

Once institutional players come aboard, one thing’s for certain—they’re looking for a return on their investment, or ROI. Regardless of financial targets, recipients of investment are obligated to deliver results to satisfy stakeholders. That kind of pressure can clash with a music-first or community-first philosophy. Several entrepreneurs told RA that it usually means boosting attendance and revenue by booking crowd-pleasing artists and increasing ticket prices, regardless of who’s in creative control.

Dimitri Hegemann, cofounder of Berlin institution Tresor, described how he’s rejected bids from corporations looking to buy rights to the Tresor brand in hopes of taking the venue global. “There was the promise that everything would be implemented the way I wanted,” Hegemann told RA. “I refused because I didn’t trust it and it was clear to me that I couldn’t do anything if a Tresor club were to be built in Buenos Aires, where only commercial interest would count. Tresor would lose its authenticity.”

Hegemann believes corporate dominance in dance music will fundamentally hinder the growth of new movements and subcultures. Others, however, seem more optimistic. When asked how Rockstar’s capital would impact Broadwick Live’s venues, a spokesperson said Broadwick has “a track record in delivering acclaimed cultural events and that hasn’t and won’t change with the investment.” Flow Festival echoed those thoughts. Private-equity backed Superstruct Entertainment, which partly owns Flow, “trusts in our artistic vision and helps us make that into reality,” a spokesperson for the Helsinki event said. Superstruct appreciates Flow’s background in underground communities, the spokesperson continued. Speaking to RA last year, UK festival Boomtown Fair also said it wasn’t worried about losing sight of its values after selling a 45 percent stake to Live Nation, Gaiety Investments (owned by Live Nation UK) and fellow promoter SJM Concerts.

Berlin institution Tresor has rejected bids from companies looking to buy rights to the brand in hopes of taking the venue global. “I refused because I didn’t trust it and it was clear to me that I couldn’t do anything if a Tresor club were to be built in Buenos Aires, where only commercial interest would count,” said Dimitri Hegemann, Tresor cofounder.

Still, many fear that a corporate presence will change the level of access for underground artists and marginalised communities. If people who don’t understand the Black and queer origins of dance music are involved in decision-making, it could ultimately hurt those minority groups. “Independent music events are more likely to reach into communities and have enduring emotional relationships but corporate interests might not be as willing to get involved with art and music or communities that don’t fit their idea of what is socially acceptable or profitable,” said Michael Fichman, a Razor-N-Tape artist and a lecturer at the University of Pennsylvania who studies nighttime economies.rali

“Is the new programming going to be inclusive? Will it impact accessibility in terms of people being able to afford to go to and be in the space?” questioned moore, who is currently writing a book on queer nightlife. “What worries me is that folks won’t be able to afford to go to see their favourite artists and that these investors and conglomerates will shape what we get to see and who is able to see it.”

All these concerns give institutional investment a bad reputation. Pushing back against this narrative are investors who claim to focus more on purpose than profit. SaveLive, a company started in 2020 by Lollapalooza cofounder Marc Geiger, former global music chief at WME, invests in small clubs around the US. Acting as a bailout solution for music venues hit by the pandemic, SaveLive takes a controlling share in each space but Geiger, in interviews, insists his deals are more of a partnership. “We don’t see this as a distressed-asset play,” Jordan Moelis of Deep Field Asset Management, a major investor in SaveLive, told The New York Times in 2020. “We see this as a business-building play, a play to be a long-term partner and to be around for a long time.”

Best Nights VC, a venture capital arm of Jägermeister, funds nightlife startups with a community-driven vision and believes financial returns can only follow once start-ups positively affect social interactions. (RA currently has an unrelated partnership with Jägermeister.) Companies under its portfolio include Feast It, a platform that connects customers with suppliers like photographers and videographers, as well as affordable audio equipment maker Soundboks.

“For many cultural entrepreneurs, venture capitalists are evil,” Best Nights VC managing director Lorrain de Silva said in an interview early this year. “We have two horns on our head because we’re capitalists, and the cultural side doesn’t fit with that.” He said he spends much of his time fighting against this stigma. “The more culturally relevant a startup is, the less it wants to be commercialised because they think they will lose their reputation if they operate commercially,” he noted. “I understand this.” At the end of the day though, great businesses need capital to grow, he pointed out.

Exploring other funding options

To avoid corporate influx, clubs, festivals and other dance music businesses need alternative financing sources. In the case of iconic London club fabric, a consortium of investors supporting the owners’ vision bought the venue in 2010. Golden Pudel formed a foundation that became the Hamburg club’s primary owner, protecting it from investors and real-estate developers.

Decentralised Autonomous Organisations, which rely on blockchain networks and the co-op model of collective ownership, are touted as a long-term solution, but until Web3 systems gain traction, more immediate solutions are needed. Existing options include The Music Venue Trust in the UK, a registered charity that protects grassroots music venues through grants. It recently completed a crowdfunding campaign called Own Our Venues that enabled fans and artists to buy community shares in venues. The Cosimo Foundation in the Netherlands, meanwhile, funds creative projects using donations sourced from redistributing deductible tax donations.

Kygo at Moody Amphitheater, SXSW.

Government funding is the most obvious answer. A lack of public help was a major reason why many nightlife and festival operators hit the brink of financial ruin during the pandemic, leaving them desperate for capital. SXSW CEO and cofounder Roland Swenson described Penske Media’s investment as “a true lifeline” in one press statement. In Montreal, a group of festival organisers that included MUTEK wrote an open letter to the government this year, decrying dwindling funding levels. Loans and grants aside, cities can also invest in independent operators by providing soundproofing to deal with neighbours, said Fichman.

Without help from benevolent private players or the public sector, corporatisation is set to continue and could even push the dance music market into bubble territory. Das from MIDiA Research believes investors will be testing the grounds over the next three years, seeing which deals fail or blow up before winners start buying out the losers. “Nightlife and dance music will become a much bigger market in value but with a lesser number of players than today,” she predicted.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.